How Exposure Therapy (Sometimes) Works

Exposure therapy and response prevention works for OCD and most phobias, but it's a lot worse at dealing with social anxiety. Why?

Part 4 of ??? in my series on abusing legitimate therapeutic techniques to deal with subclinical social anxiety.

The Test Is In One Hour

Two high school students are about to fail a test. To be clear, they know they are almost definitely failing — they haven’t studied, they don’t know the material, and the test is in one (1) hour. The outcome of the test determines whether they’ll get into their dream college.

Student A has their textbook. They could theoretically cram. Maybe they should?

Student B lost their textbook yesterday. No way to get it back before the test.

Student A is clearly in an objectively better position. This student strictly has more tools that he could be using to pass the exam. So logically he should be less stressed out, right?

No. The student with the textbook is going to be freaking out, obviously. He has to sit there for an hour flipping through the textbook in front of him, knowing he SHOULD be cramming more effectively, knowing he COULD be trying harder, drowning in the guilt and anxiety of not perfectly optimizing his doomed effort. Every minute that passes is another minute he’s failing to use properly, even as he frantically skims passages in the hopes that something useful might lodge in their memory.

Student B? He doesn’t have a textbook. There’s nothing to be done. Might as well get coffee before the exam.1

Afterwards, the two students learn that against all odds, they both passed their exam. The students draw these lessons:

Student A: Yes! Cramming works!

Student B: Wow, I guess I never needed to cram or study after all.

Why Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Responds To Exposure Therapy

Someone with contamination OCD washes their hands 47 times a day. Their feared outcome is clear: contamination leads to illness/death. The hand-washing is their version of the useless textbook: a tool that feels like it will probably work to prevent illness and death but only if they use it as hard as possible.

ERP (Exposure and Response Prevention Therapy) for OCD is simple:

Expose them to the “contaminated” doorknob (Exposure)

Physically prevent hand-washing (Response Prevention)

Wait

They don’t die

Brain updates: “Oh shit, maybe doorknobs aren’t deadly”

The key is that the feared outcome (getting sick) is falsifiable. You can actually test whether touching a doorknob makes you sick. It doesn’t. Prediction error occurs. Learning happens.

The response prevention part is crucial. If they wash their hands even a little bit, they’ll attribute survival to the washing. The learning only happens with complete prevention of the safety behavior.

The Habituation vs Inhibitory Learning Model of ERP

The field used to think exposure worked through habituation — you sit with the fear long enough, your anxiety naturally decreases, and eventually you’re “cured.” Like getting used to cold water. The idea was that fear just wears off through repetition, like your nervous system gets bored.

To be clear, this definitely does happen to a degree. But this model never fully explained why people would improve in therapy but then relapse at the slightest trigger. If you were truly “habituated,” why would the fear come roaring back later on?

The current model — inhibitory learning — tells a different story of how permanent improvement occurs: namely, via belief disconfirmation. Your brain has to predict something bad will happen if you touch that doorknob and then don’t wash your hands, and then it has to experience that it doesn’t. The prediction error specifically is what drives long-term learning. No prediction error, no overriding long-term memory formation, no lasting change.

This is why response prevention is so critical in OCD. If you wash your hands after touching the doorknob, there’s no expectancy violation. Your brain goes: “I touched the doorknob and washed my hands and didn’t die. See? Washing works! Which is great because doorknobs are deadly.” But if you can’t wash? Your brain predicts death or illness, experiences neither, and the prediction error gets recorded.

This model explains why ERP works so well for OCD and specific phobias. “I’ll get sick if I touch this doorknob and don’t wash my hands” — falsifiable! “The plane will crash if I’m on it” — also falsifiable!

Social Anxiety Does Not Fit This Model Because The Relevant Fears Are Mostly Unfalsifiable

But for social anxiety? The core fear is “they’ll think I’m weird.” How do you violate that expectancy? You can’t. There’s no observable outcome that contradicts the prediction. You leave the party with zero information about whether your prediction was accurate. No prediction error, thus no inhibitory learning, thus no new memory to compete with the old one. (Frequently, anyway. You can sometimes get positive or negative information about how things went, for instance if someone says “Wow Aaron, you sure were normal today!” Sweet sweet validation. So good. But this is very unusual.)

Which brings us to the question: if a tree falls in the forest and nobody’s around to hear about how much the tree absolutely hates me personally, should I care about its opinion? But let’s move on.

Also We’re Mostly Not Doing Response Prevention LOL

Response prevention for social anxiety is basically impossible for researchers to measure in any principled way.

OCD response prevention: Don’t wash your hands! Observable. Unambiguous. Either you washed or you didn’t.

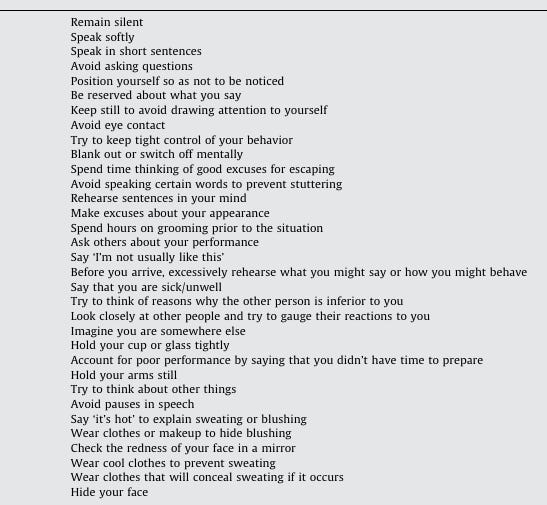

Social anxiety “response prevention”: Well… there’s a whole-ass questionnaire called the SAFE that includes these items in its attempt at a full inventory of social anxiety safety behaviors which need to be prevented:

How can you ask someone to not “blank out” or to not “Try to keep tight hold of your behavior?” How could participants even tell if they did this in retrospect? (Did I blank out today in dance class? Would I remember if I did?)

You can ask patients to restrict a subset of these behaviors, which is probably broadly analogous to ripping out all the even-numbered pages in Student A’s textbook. Does it help? Probably. But not, you know, a lot; the student can just focus his attention on memorizing the remaining pages. And a lot of these behaviors are rather strong compulsions— you know when there’s an awkward silence and you just have to fill it with words? It takes a genuine effort of willpower to not do that.

Researchers are trying. They’re trying so hard.

And they’re failing.

Social Mishap Studies Are Cool But Very Mild Interventions

There’s a thing called “social mishap studies.” They feature patients intentionally fucking up socially in very tiny ways: spilling a drink, perhaps, or in one study giving a speech and intentionally pausing for five full seconds during the presentation. The point being to demonstrate to the patient that their absurdly perfectionistic standards for social interaction aren’t necessary or useful.

I would classify this, I think, as the same kind of exposure therapy except with really good response prevention; it’s just that instead of “preventing the patient from attempting to managing their image” (tricky, as discussed) this goes a step further and dictates the patient actively sabotage their image in a very small way.

Great idea, in concept. The only real problem with these is that the most commonplace kinds of social fear are around stuff like “what if I express an opinion that someone finds distasteful,” which (as anyone online over the last ten years can tell you) has substantially wider variance in outcomes. “What if I ask my coworker out and make it weird?” “What if I ask to join someone for lunch and they accept and then I’m just kind of this weird intruder?”

I mean, it makes sense therapists don’t prescribe these actions. Think of the liability! Think of the IRB approval process, my God. “As part of the proposed treatment protocols we will have the client maybe self-immolate socially and get dragged on social media.” Yeah, that ain’t happening.

So everyone’s doing their best. Even so, it does mean fundamentally we are doing exposure therapy using “exposures” that none but the most anxious people actually give a shit about. And in fairness, researchers studies social anxiety disorder are primarily concerned about people who are so socially anxious they cannot function in society.

This Is Not New Information

Standard ERP for social anxiety has a methodology that’s fundamentally mismatched to the problem.

And the field already knows this. This is exactly why the state-of-the-art treatment for social anxiety isn’t pure ERP — it’s Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and, more recently, Metacognitive Therapy (MCT). These approaches target what pure ERP can’t touch: the threat-scanning, the rumination loops, the post-event processing where you replay every microsecond of that conversation at 3 AM.

CBT goes after the catastrophic interpretation. “Everyone thinks I’m an idiot” becomes “Some people might think I’m awkward, and I’ll survive that.” This is considered the modern state of the art for social anxiety, which is unfortunate because remission rates from CBT done for social anxiety disorder are at 40%, which is… not great.

MCT goes even further. Stop analyzing whether that laugh was at you or with you. Stop trying to reconstruct what your face did during that presentation. Stop luridly imagining the conversations behind your back about how cringe you were at the party. The content of the worry is nearly irrelevant; big chunks of the therapeutic protocol involve exercises that teach the patient that they can stop worrying about stuff and nothing that bad will come of the lack of worrying.

Let’s come back to Student A, getting advice from these different methodologies about how to be less anxious before tests:

ERP By Itself: “Just keep taking tests and eventually you’ll start to relax.”

CBT: “Failing this test isn’t the catastrophe you think it is, so try to calm down. Let’s design some experiments to help you realize this fact.”

MCT: “Stop thinking about the exam. You will pass or fail and that is largely beyond your control; rumination about failing the exam is causing you to do weird compulsive behaviors that sabotage your performance. Cramming from the textbook is banned.”

CBT seems to work much better than ERP alone; MCT seems to work better than CBT for anxiety disorders generally.

The textbook was never going to save them anyway; the textbook is basically a lie. The illusion of control.

Why would CBT work?

Social anxiety safety behaviors— filling up silence, clutching drinks, and so on— are downstream of you, deep down in your gut, believing that if you don’t do them you will embarrass yourself. However, public embarrassment is survivable, and to the degree you can chill out about public embarrassment (which CBT tries to help you do), you will naturally stop doing the safety behaviors; this results in the social anxiety abating.

Why might MCT work better?

I suspect the most damaging safety behaviors are the mental rumination processes: planning out conversation topics, monitoring peoples’ faces to figure out if you said something cringe, making conversational flowcharts. And the impulse to perform them is maintained by post-event rumination on how people feel about you; this keeps the feeling of threat alive in your psyche. MCT is extremely focused on banning all of these.

The True Form Of Social Anxiety Exposure Therapy

The vast majority of safety behaviors listed in the SAFE questionnaire are downstream of the desire to improve how observers see you.

ERP, whether for anxiety disorders or OCD, requires banning all safety behaviors to be effective, otherwise you’re either teaching yourself “everything’s fine as long as I engage in all these safety behaviors” or (even worse) “that would have gone better if I had just engaged in yet more safety behaviors.”

You can see where I’m going with this. This implies doing social anxiety ERP for reals involves exposing yourself to social situations while doing nothing whatsoever to consciously manage your image in-the-moment. No agreeing with stuff to be agreeable. No filling awkward silences. Manspread. Slurp your drink, noisily. Embrace whatever awkwardness occurs. But you also still need to engage meaningfully with others; avoidance is just another safety behavior. ERP will be effective to the degree the patient can be made to do this, but doing this is really really hard if you’re anxious because it feels like you’re going to die.

Which is why social anxiety treatment is such a hard problem in the literature.

FAQs

Wait, you basically left off the whole thing about how people sometimes don’t like you.

This, too, is a big issue in exposure and response therapy for social anxiety: sometimes the feared event comes to pass totally unambiguously!

But I don’t think this explains much, not really. Many people have lots of acquaintances who dislike them yet have little obvious anxiety about the fact. I suspect social anxiety might be symptomatic of having a fragile sense of self that is significantly dependent on peoples’ opinions; which isn’t as damning as it sounds, really, since I think a sense of self can be developed. And I suspect one develops it by cultivating the art of saying stuff you think is good and true and letting other people deal with it (politely).

Excuse me, but there can be real life consequences for not being liked.

This is true. Sometimes.

Social anxiety takes the distribution of responses people might have to you and compresses it into the safest possible median. No one hates you, no one loves you.

For some contexts, this is optimal! If you’re in middle management, politics, or academia, minimizing downside risk might matter more than maximizing upside potential. “Will this tweet be screenshotted and used against me in several years?” If you’re in academia, uh, maybe?

(Though this point, too, can be oversold. Kamala Harris vs Donald Trump was a pretty good case study of utterly polished hiding-of-self vs totally open and unabashed displaying-of-self in politics. Empirically, voters were willing to take someone openly corrupt and megalomaniacal over three consultants in a trenchcoat. Which was, of course, to America’s massive detriment. But this isn’t a politics blog; let’s move on.)

The problem is that social anxiety applies this academia-level paranoia to parties, creative work, and especially dating, where it’s deeply counterproductive. You ever read that romance novel where the protagonist girl falls for a mid guy with no obvious virtues or flaws? Excuse me harem anime don’t count that’s a whole different genre thank you.

Anyway, the real question isn’t “is social anxiety irrational?” (sometimes it isn’t) but rather “can we develop the capacity to consciously choose when to compress our personality distribution?” Can we be deliberately boring in faculty meetings and deliberately weird at parties and on dates? Social anxiety is just you having your surveillance paranoia permanently turned on, even when you’re just trying to find your people.

MCT might just work better than CBT because, instead of trying to improve the accuracy of your surveillance mechanism, it shows you that you can and sometimes should turn it off.

Why did you write this, exactly?

I see frequently that even well-informed people talk about “exposure therapy” as though it were literally just about exposure to a feared stimulus. But it’s not: it’s exposure and response prevention, because the implicit belief that you need to scramble frantically whenever the feared stimulus arises (the “response”) is at the core of why the person is anxious in the first place. Just telling someone to go to parties until they chill out is not exposure therapy.

Does the literature actually support your clear preference of MCT over CBT?

Kind of? Studies comparing the two (for anxiety disorders) show either parity between CBT and MCT, or show MCT as being better. However, all studies comparing the two methodologies IIRC are run by a pretty small group of core MCT researchers, so we should take this with a grain of salt. See also Solem 2021, Nordahl 2018, Rawat 2023.

Adrian Wells initially pioneered MCT because of flaws That said, Wells specifically pioneered metacognitive therapy years after being a practicing CBT therapist because he noticed that frequently his patients in CBT would get through disconfirming one fear only to spontaneously develop totally new fears that also needed disconfirmation, in a chain that continued seemingly forever, and developing MCT was his way of trying to kill this game of whack-a-mole at its source.

Which seems reasonable enough. And since the MCT theory of change aligns closely with my experiences, I’m willing to take its suboptimal evidence base at face value. The replication crisis in psychology is very, very real, which means we are forced a lot more into first-principles and introspective reasoning a lot more than would ideally be the case. Caveat lector, I guess.

According to the book Lying For Money (delightful read, highly recommended), fraudsters engaged in long-running Ponzi schemes frequently report being relieved after their fraud is discovered. Because then they can stop frantically trying to hide it.

How about explicit instruction in successful social behaviors? An acting class, basically. Would that help?

Or, alternatively, changing the game. Success is spending an hour at the party, not anything that happens during the party.

"You ever read that romance novel where the protagonist girl falls for a mid guy with no obvious virtues or flaws?" >> So I feel like this really does happen! Attraction can be very idiosyncratic and can depend a lot on people being good but not showy. Anybody else?